Aniela (Lela) Pawlikowska Comes out of the Shadows by Anna Pawlikowska

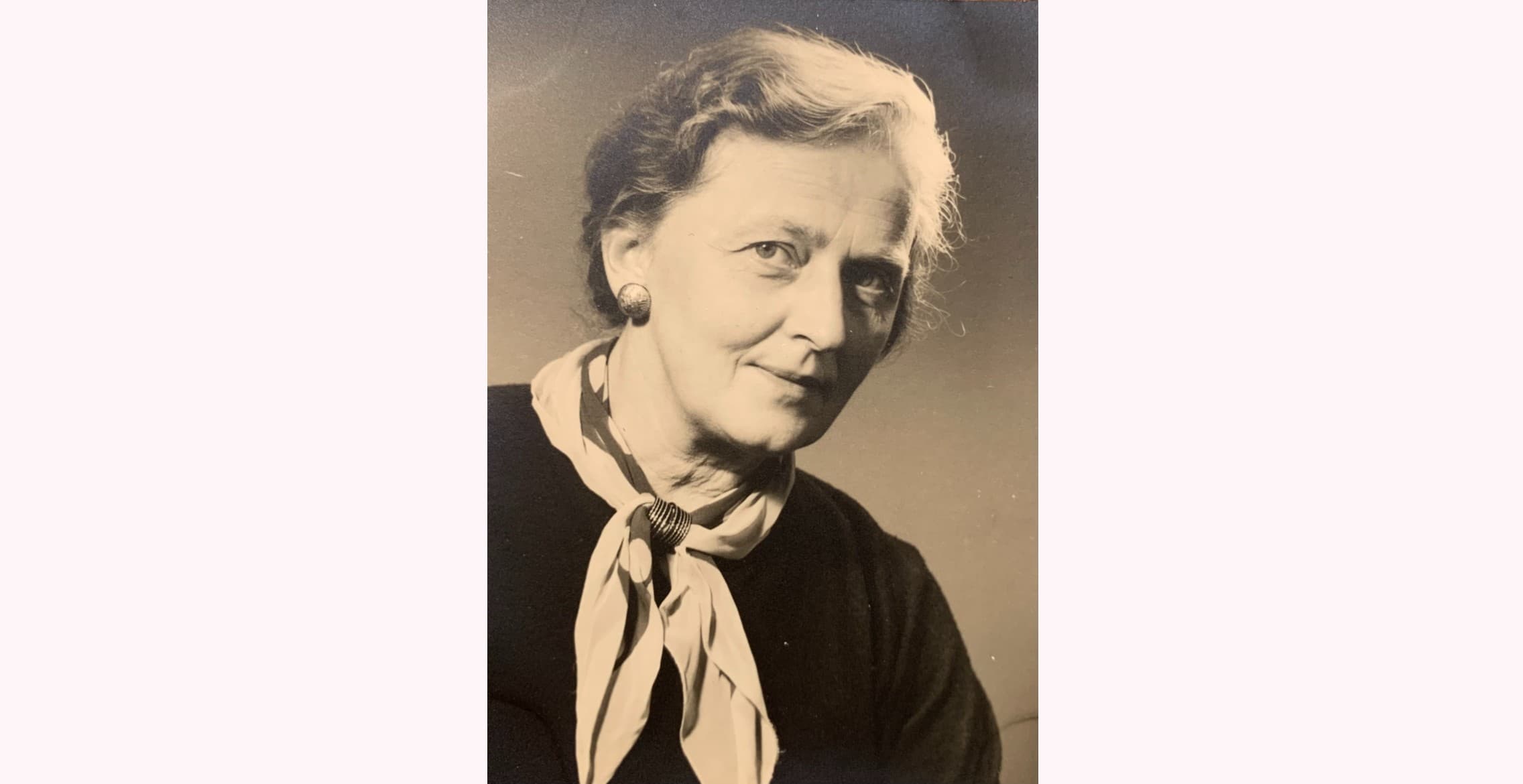

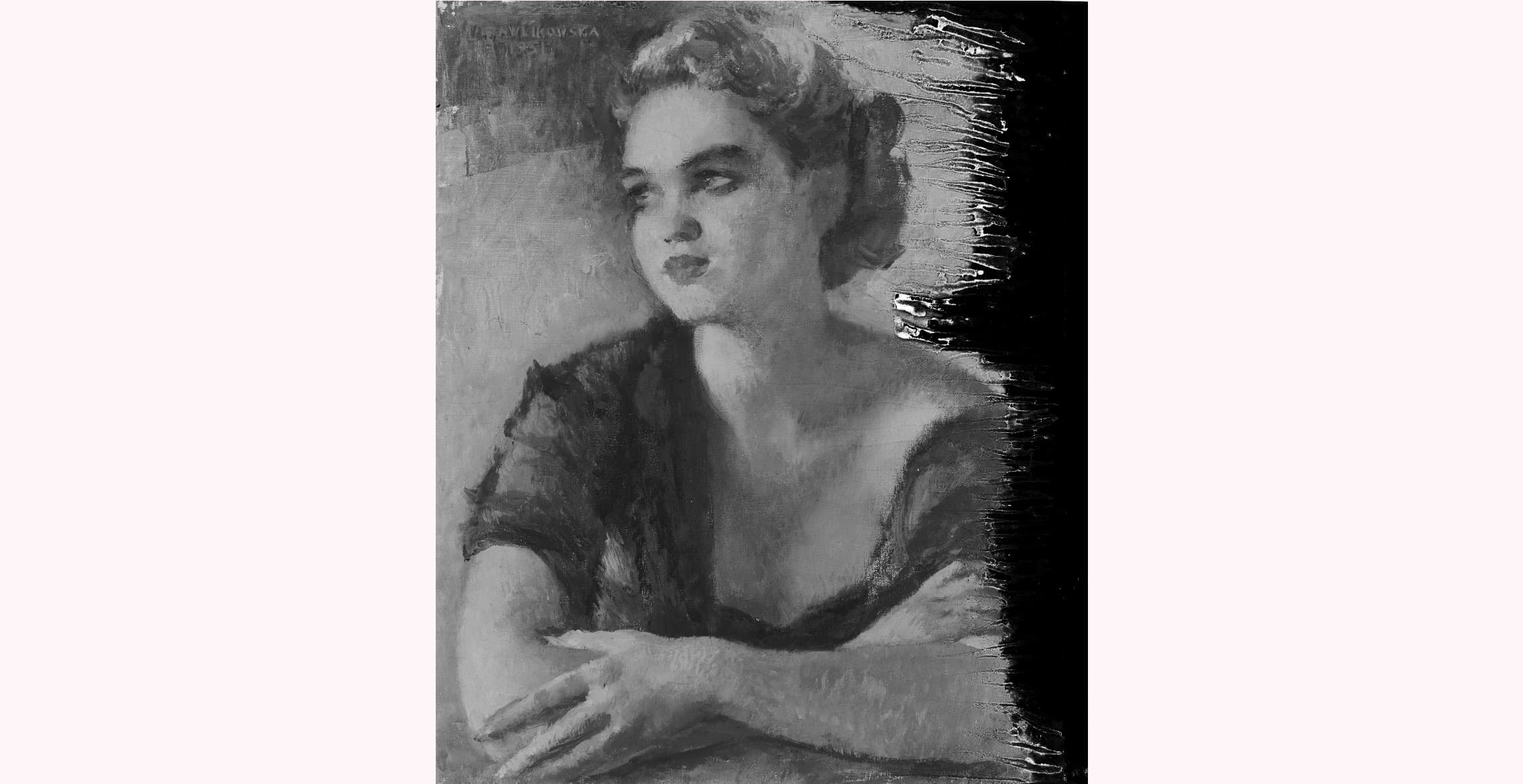

Why is it that an outstanding portraitist and brilliantly self-educated artist such as Aniela (known as Lela) Pawlikowska [Fig. 1] remains a virtually unknown figure today? How is it that we still know so little about her, despite several individual exhibitions held in Poland in the last 20 years, and the publication of Marta Trojanowska’s groundbreaking monograph (2021)?

Several factors have contributed to this state of affairs. I will try to explain them here, introducing Lela Pawlikowska’s oeuvre and achievements.

Family background, lesser position, maternal inheritance passed on to the sister

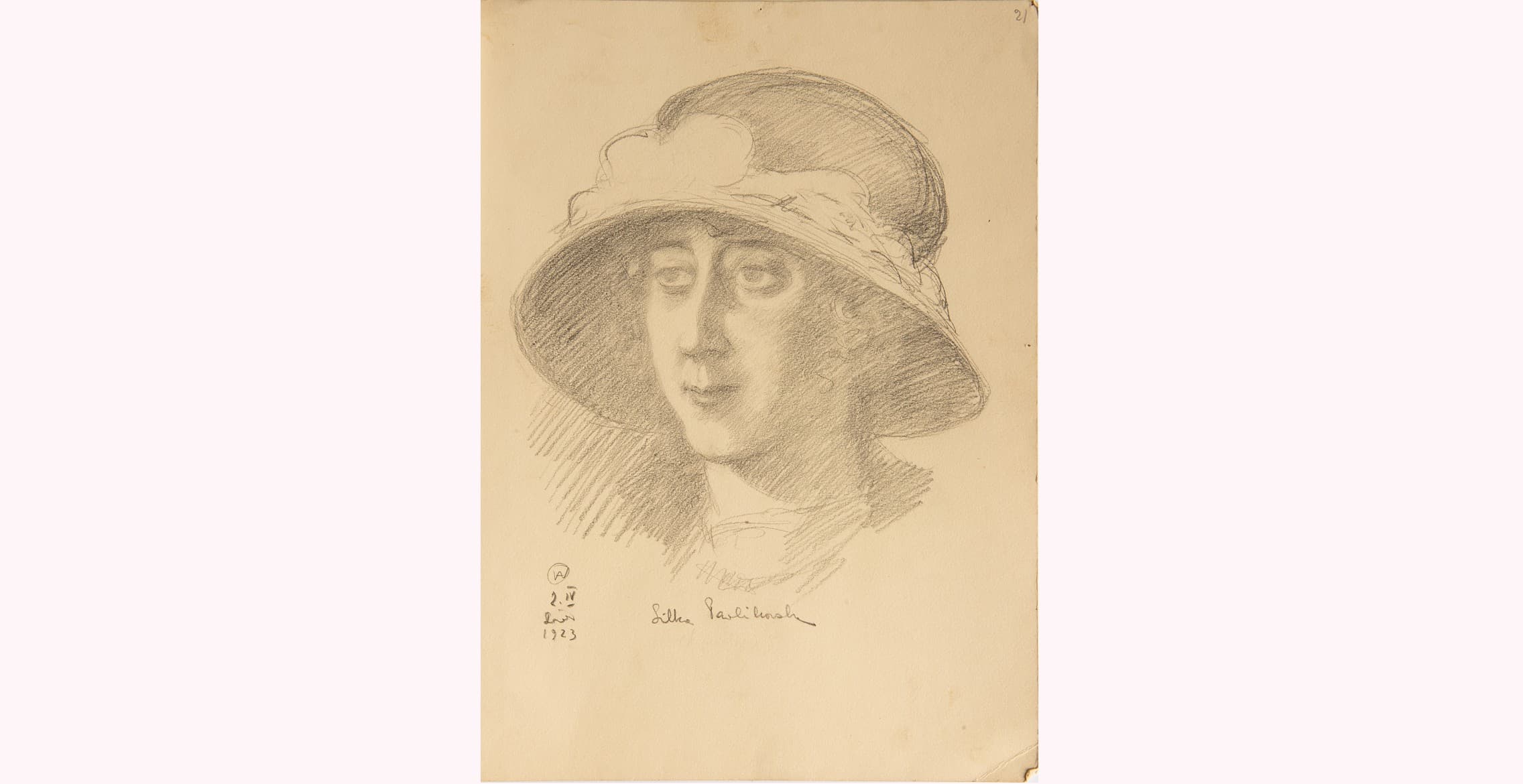

Pawlikowska’s upbringing was no doubt one of the reasons for her near oblivion. Lela (née Wolska) was born in Lwów [Lviv] in 1901 to a remarkable family. Her mother, Maryla Wolska, was a famous poet of the Young Poland period, herself the daughter of Wanda Monné Młodnicka. Monné Młodnicka was, in turn, a writer and translator, but above all, the legendary fiancée of the famous and talented painter, Artur Grottger, who tragically died before their wedding. It was the weight of that tragic death that turned Wanda Monné Młodnicka [Fig. 2] into a priestess of his memory and achievements, thus making her independent of the patriarchal corset of family relations at the time.

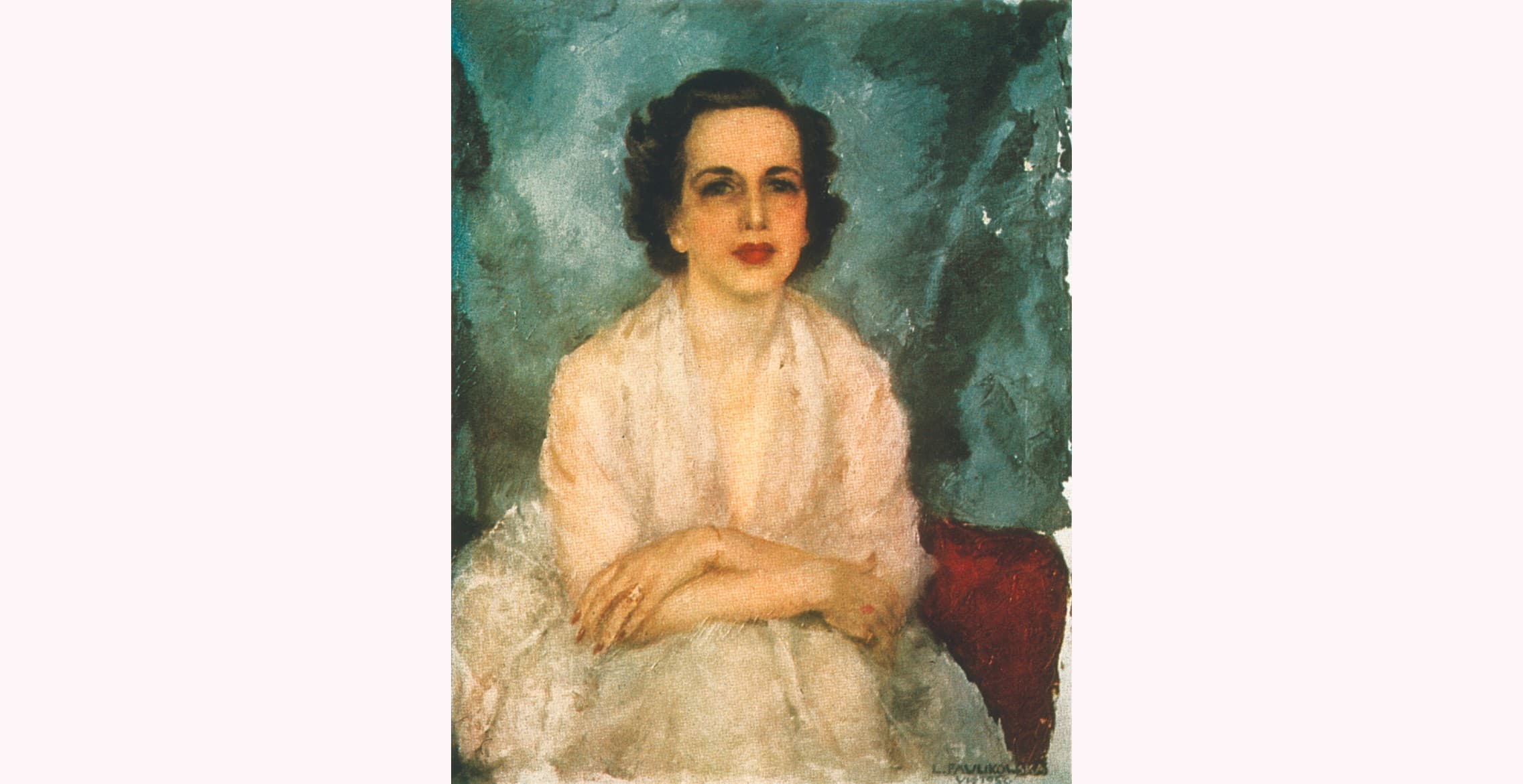

She handed down that baton to her daughter Maryla, who was brought up in freedom unknown to girls in the second half of the 19th century. Maryla’s [Fig. 3] sole task was her own artistic development. (Though she failed in the field of art, she found success in literature.) Wanda guarded her daughter’s creative freedom for years; later she even enlisted Maryla’s husband, Wacław Wolski, an engineer and inventor, and father of their five children, to provide her with as much time as possible for her poetry. Among their children, the legacy of social independence and a commitment to artistic obligations fell to the poet Beata Obertyńska, the elder of the two daughters. Maryla loved Beata [Fig. 4], who shared her literary inclinations, and devoted considerable attention to her daughter’s educational development.

Aniela (known as Lela), the youngest of the siblings, did not receive this privilege. While the three Wolski brothers were formally educated in schools and gymnasiums, the sisters were afforded only the haphazard home schooling that was customary for girls at that time, making it impossible to pursue more advanced formal studies. [Fig. 5]

Moreover, Lela’s artistic abilities did not arouse much interest in the family. However, those abilities were recognised by the eminent psychologist and art teacher Władysław Witwicki, who decided to include Lela’s pictures in the 1910 Lwów exhibition Art and Child, which was reviewed in the press. Among some one thousand children’s works sent in from all three partitions of Poland, as many as fifty-four drawings of the eight-year-old Lela were shown, which did not go unnoticed by art critics.

However, this did not change Lela’s situation at home. It seems all the stranger in light of the fact that Maryla herself – long considered the successor of the artistic talent of both her father, and even of her mother’s one-time fiancé Artur Grottger – had been sent to study painting in Paris and Munich. Instead, Lela remained in the shadow of her sister, her artistic education having been limited to drawing lessons provided on occasion by Władysław Witwicki.

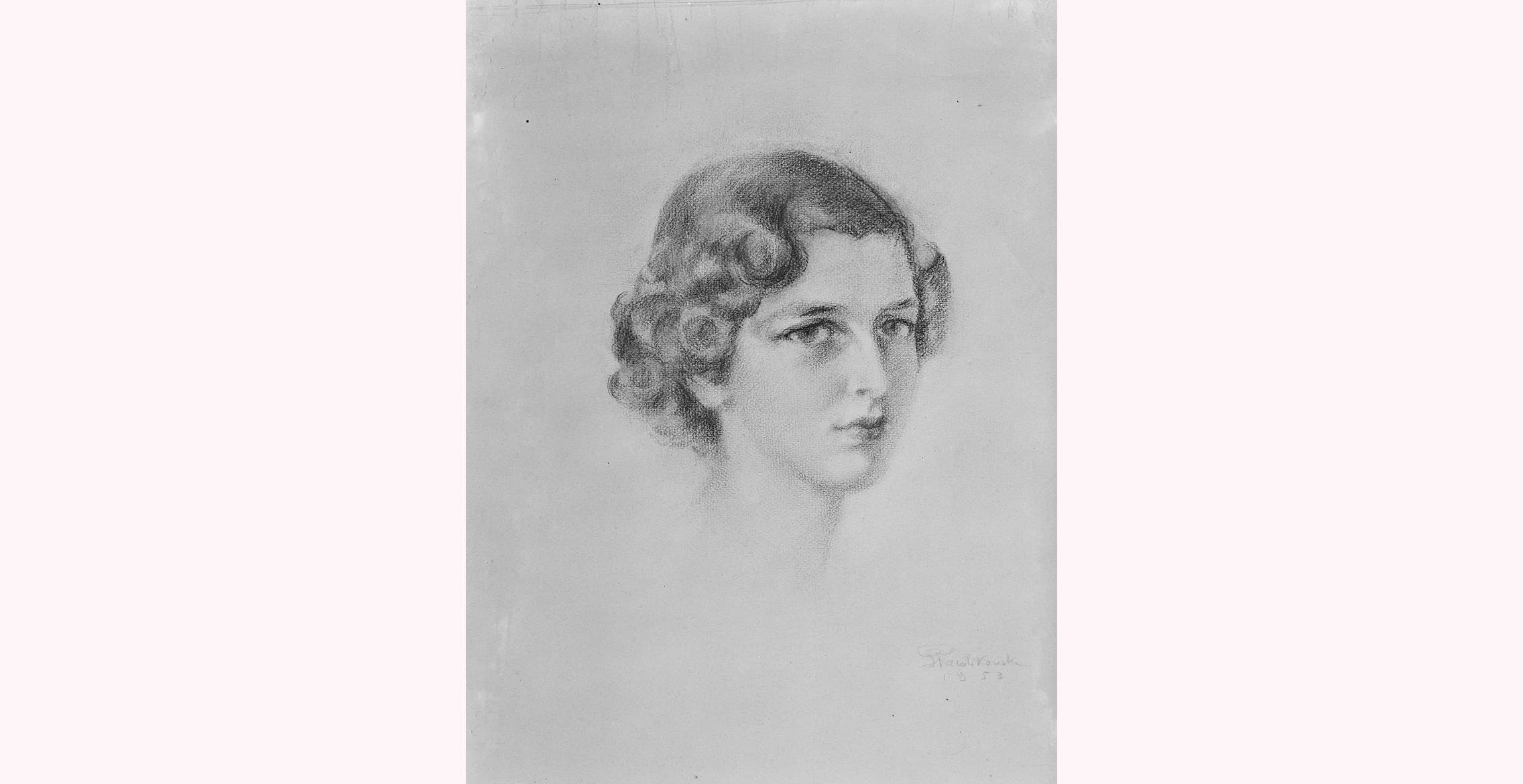

Lela’s early adulthood [Fig. 6] coincided with turbulent times. After the tragedy of World War I and its direct impact on the Wolski family, peace in Lwów remained elusive. First, the war swept through the city and its surroundings – alongside the newly created Ukrainian state. Maryla’s eldest, beloved son, was tortured and executed for writing an anti-Ukrainian poem. Polish-Ukrainian tensions had not subsided when a bloody war with the Russian Bolsheviks broke out only to end in the fall of 1920. These events no doubt negatively impacted the already marginal education of the Wolski girls. And yet, in newly independent Poland, Lela was able to attend art history classes as an unenrolled student at the University of Lwów, take clay modeling lessons from Luna Dexler, and put much work into historic costume studies. Her efforts to obtain a more thorough education seemed largely self-directed.

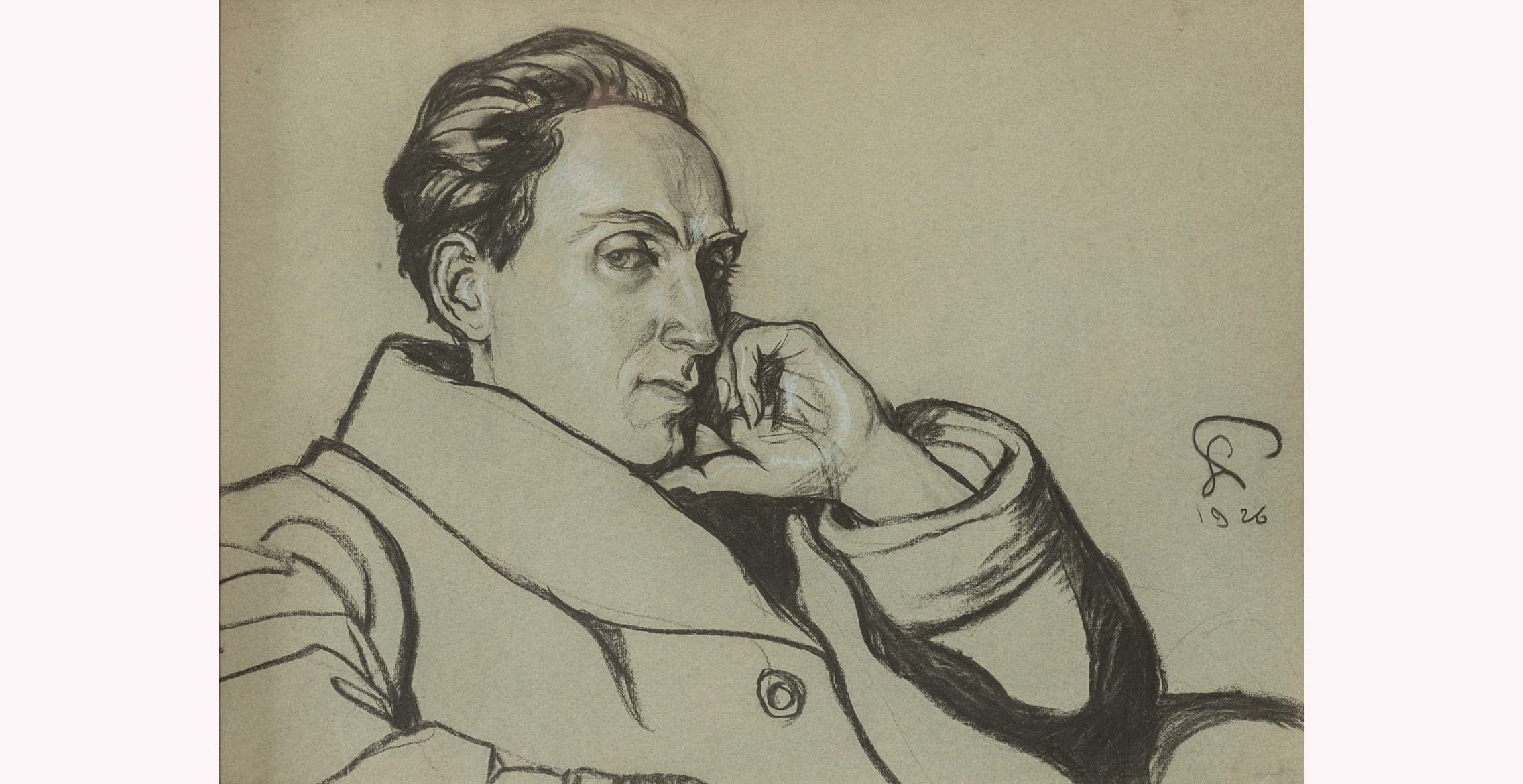

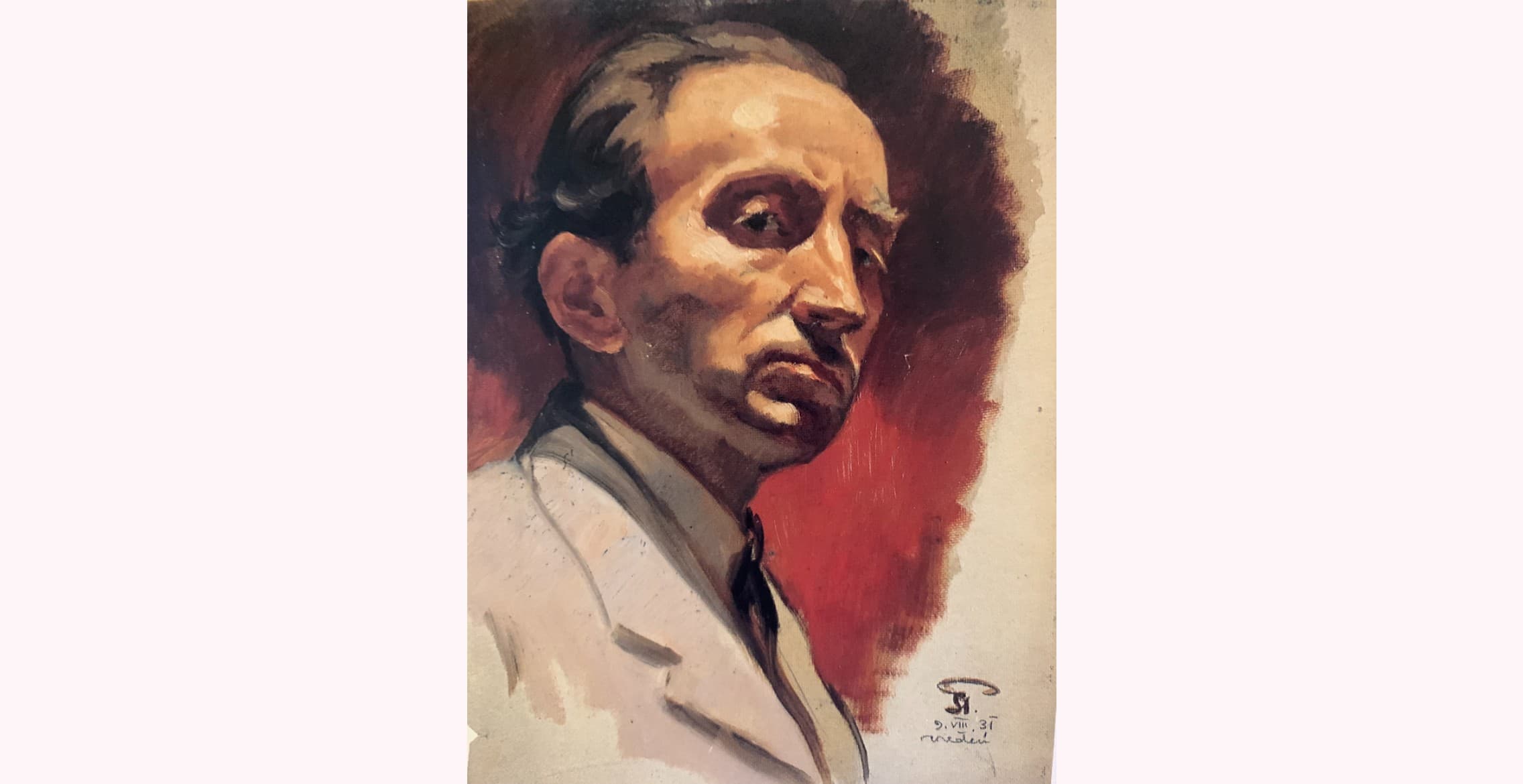

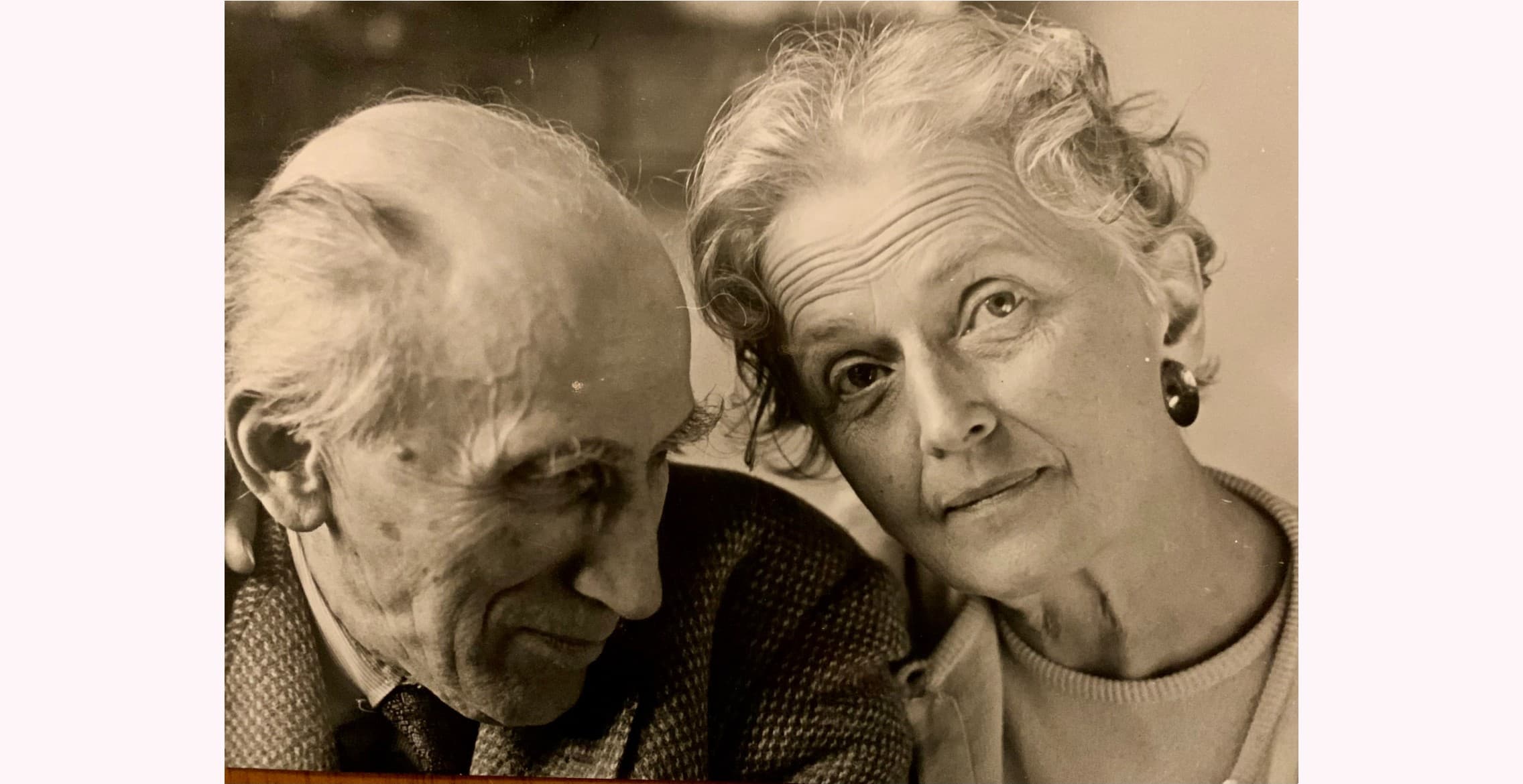

This situation changed radically when she met Michał Pawlikowski [Fig. 7], who was 14 years older and already once married and divorced. His family had been on friendly terms with her family for several generations. Lela and Michał’s wedding took place on 9 February 1924. They settled in Medyka, at the Pawlikowski family estate, where they had five children over 13 years. (One died at the age of two, another in 1944.) Thanks to her husband’s encouragement and support, Lela experienced intensive artistic growth during this period.

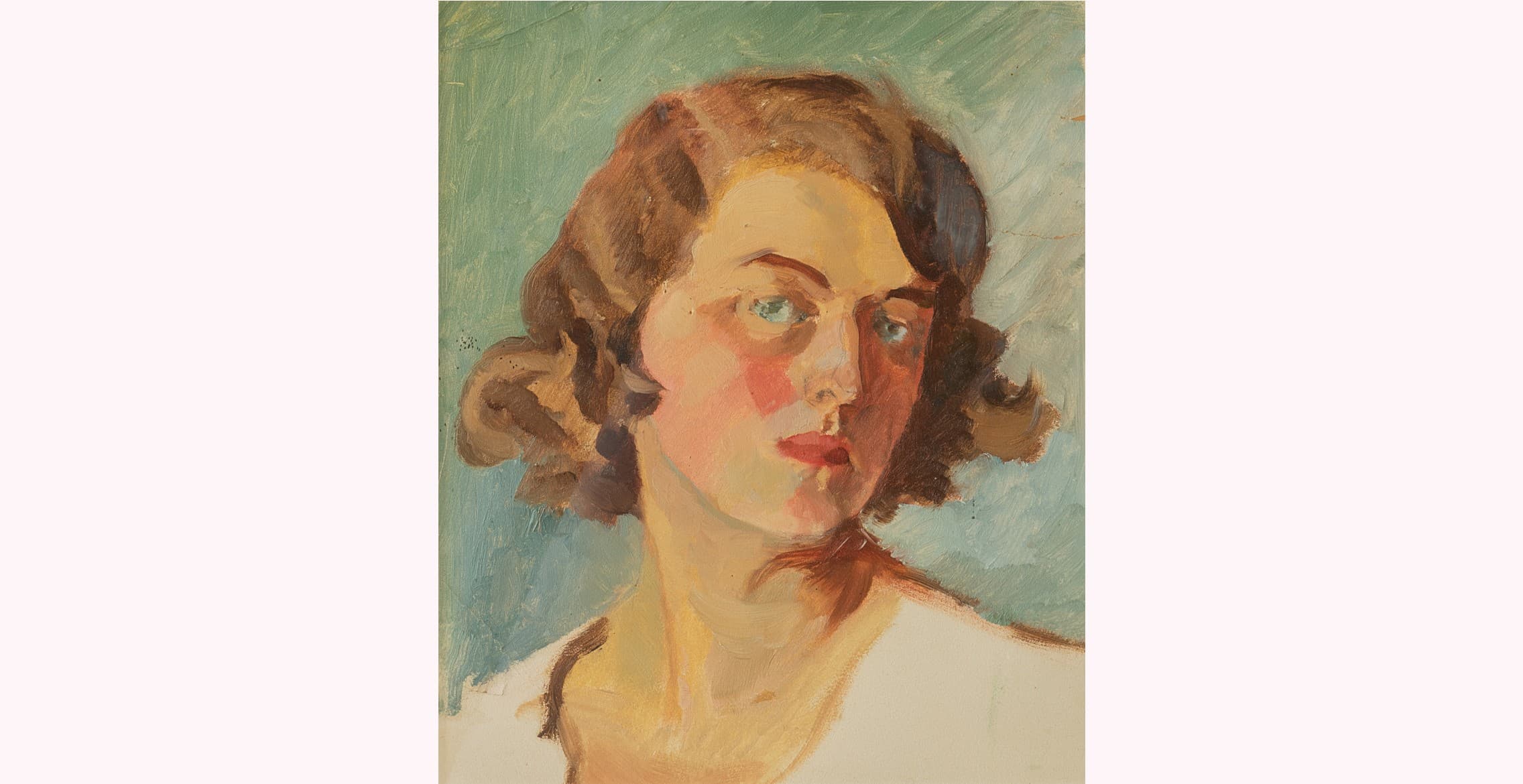

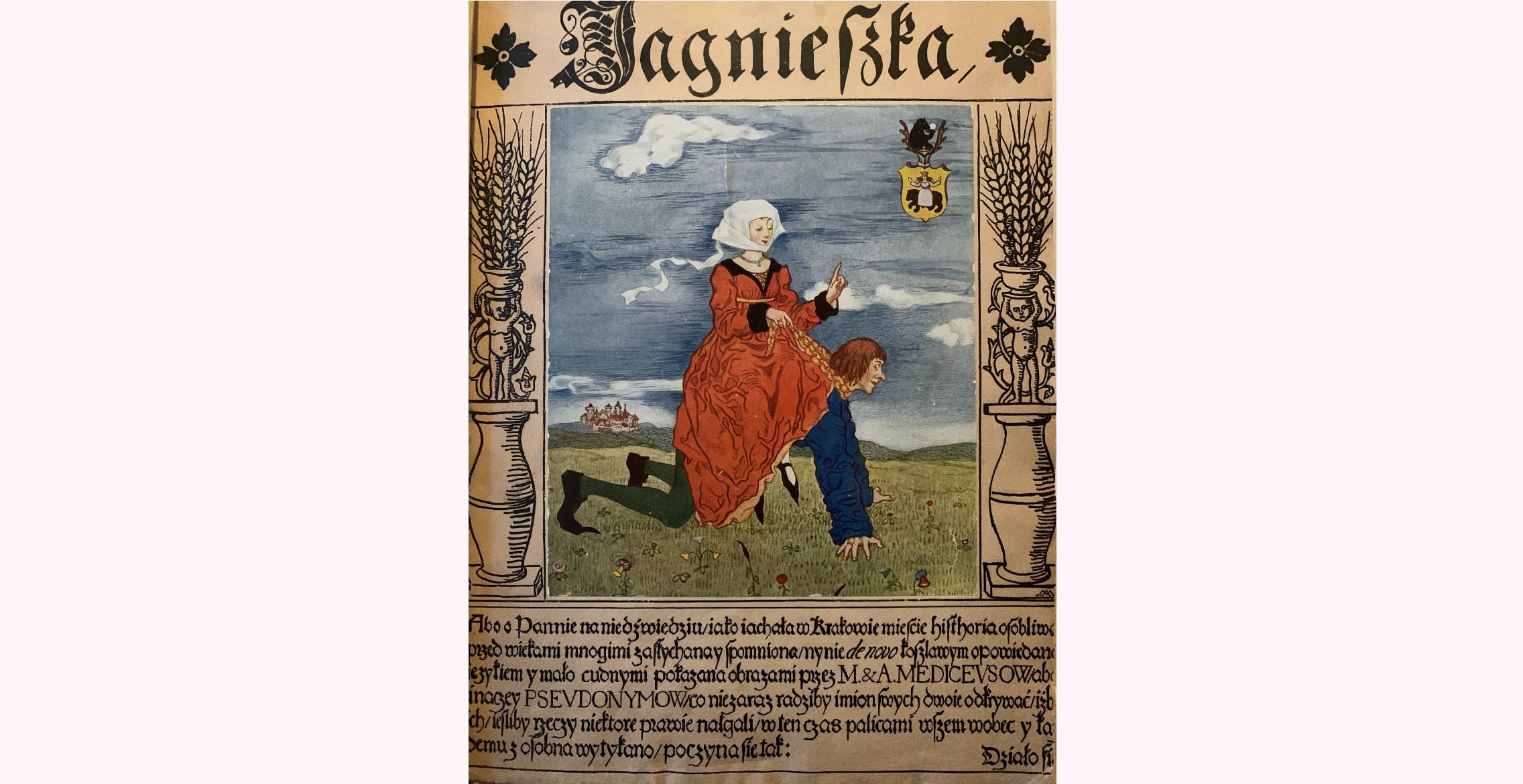

She made her debut in 1925 as an illustrator of Jagnieszka, a historical fiction novel written by Lela and Michał together, stylized in medieval print and published by Pawlikowski himself [Fig. 8]. Lela’s talent and deep knowledge of costume design were soon noticed even in England when a note about her illustrations, along with a full-page reproduction, was published in The Studio magazine. In the early 1930s, she studied for two years as a freelance student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków.

Her husband not only encouraged her to continue her studies, but also documented her artistic achievements in his diaries, collected photographic reproductions of her paintings, facilitated her participation in exhibitions, responded to reviews, and even helped her with producing larger linocuts. Until the beginning of World War II, Lela gained recognition as a portraitist, illustrator and author of a monumental series of religious prints. She took part in over 20 group exhibitions, including oversees, and her paintings won awards and generated numerous favourable reviews.

But her husband’s patronage also had a darker side [Fig. 9]. Michał was overbearing, domineering and a contrarian, seeing himself as the most important judge of his wife’s works. On the backs of many of her paintings, one can read his critical commentary concerning the mimetic quality of a given work. In the Polish Biographical Dictionary, his entry reads: ‘an opponent of cosmopolitanism in art, he demanded national art.’ Even after his death, which predated hers by ten years, he remained her most important authority.

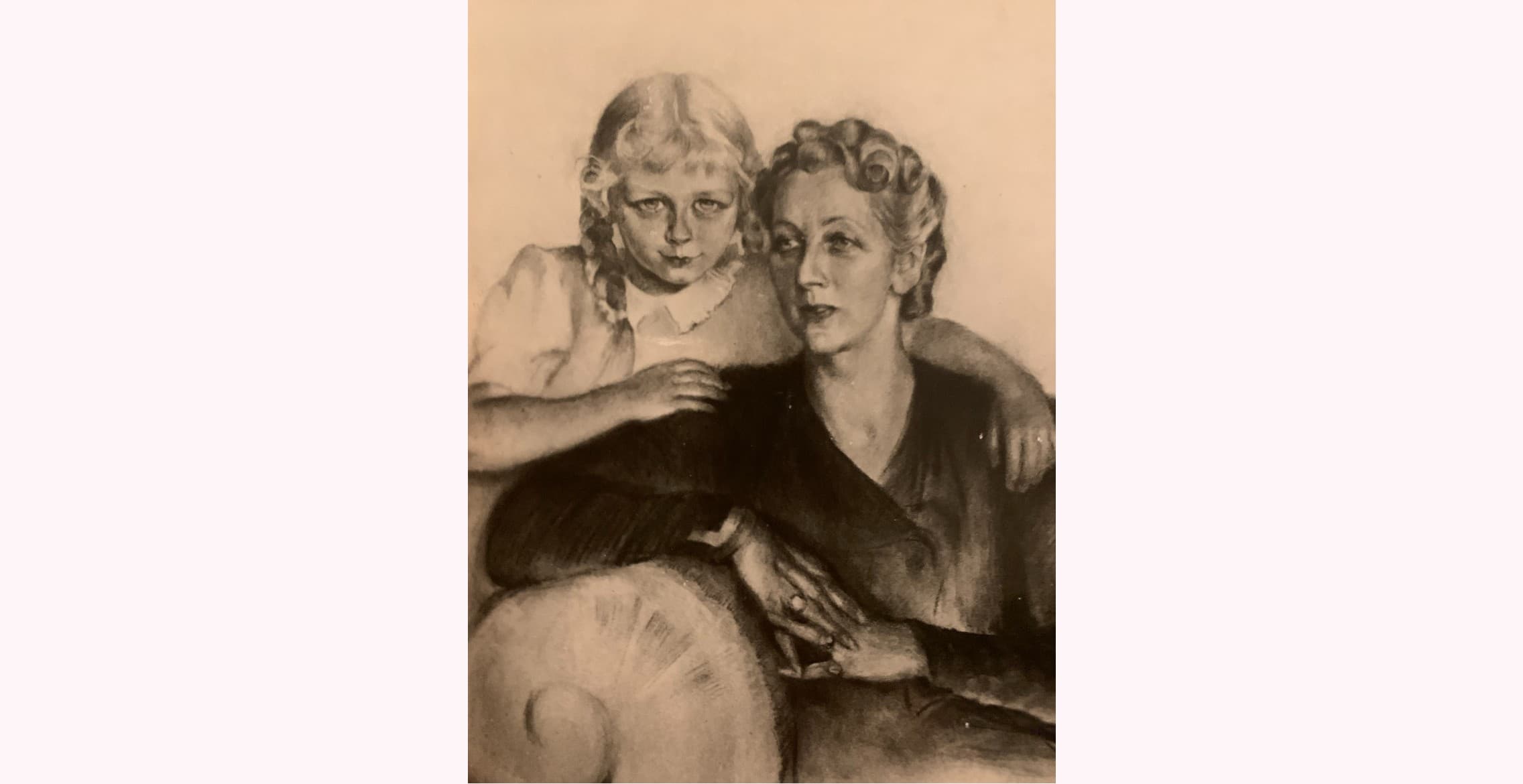

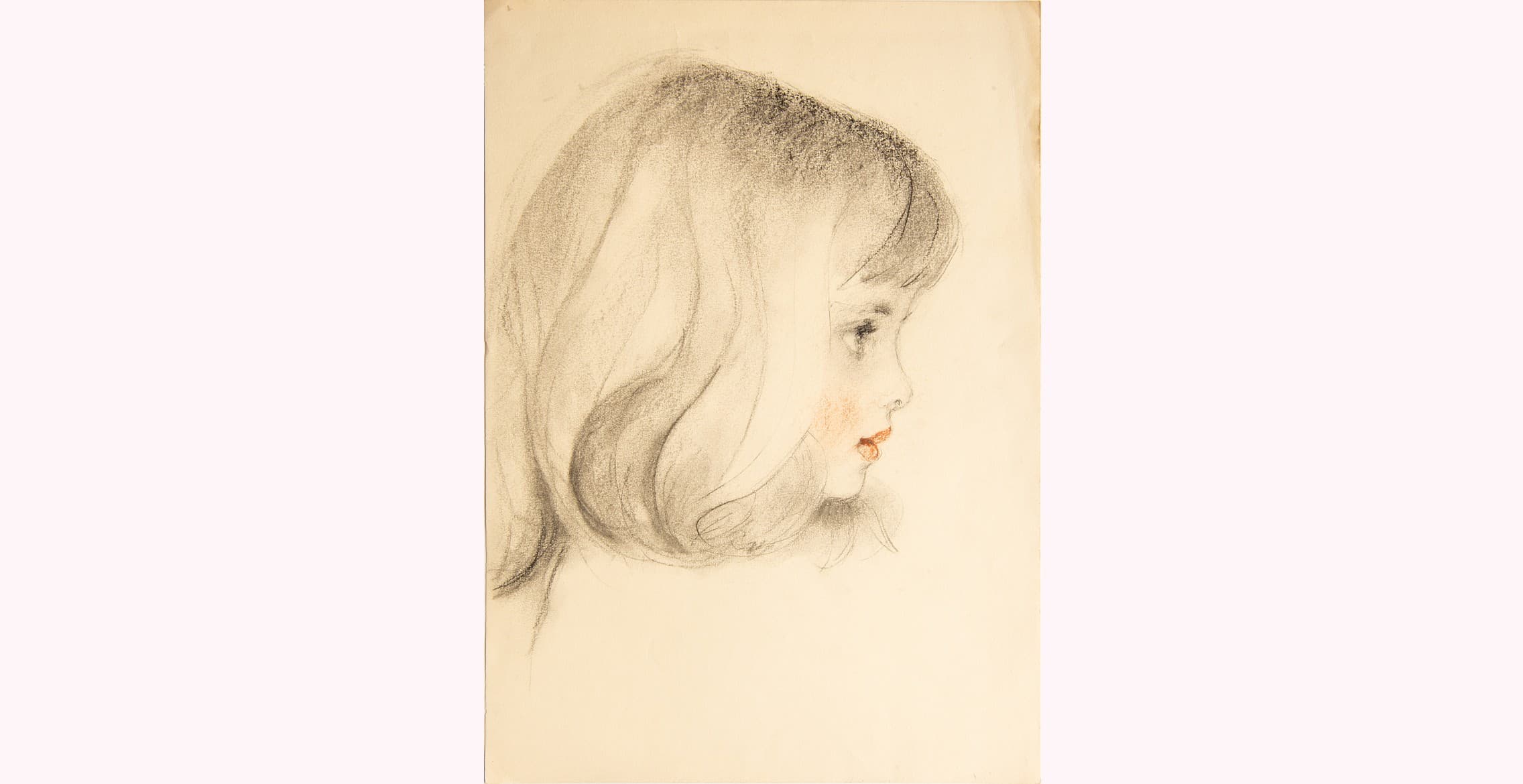

Nonetheless, Lela Pawlikowska was able to overcome such obstacles, leaving an impressive artistic output. In the interwar period, her most important achievements included her first published illustrations for Jagnieszka; a series of portraits, like the award-winning Portrait of Mrs. Szajnochowa (1933) [Fig.10]; Portrait of Iza Boniecka, a portrait of her sister-in-law Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska [Fig. 11]; excellent portraits of children (Lula in a blue dress, early 1930s [Fig. 12] Kasper [Fig. 13], Lula and Kasper [Fig. 14] Agnieszka [Fig. 15]; and a few marvellous self-portraits.

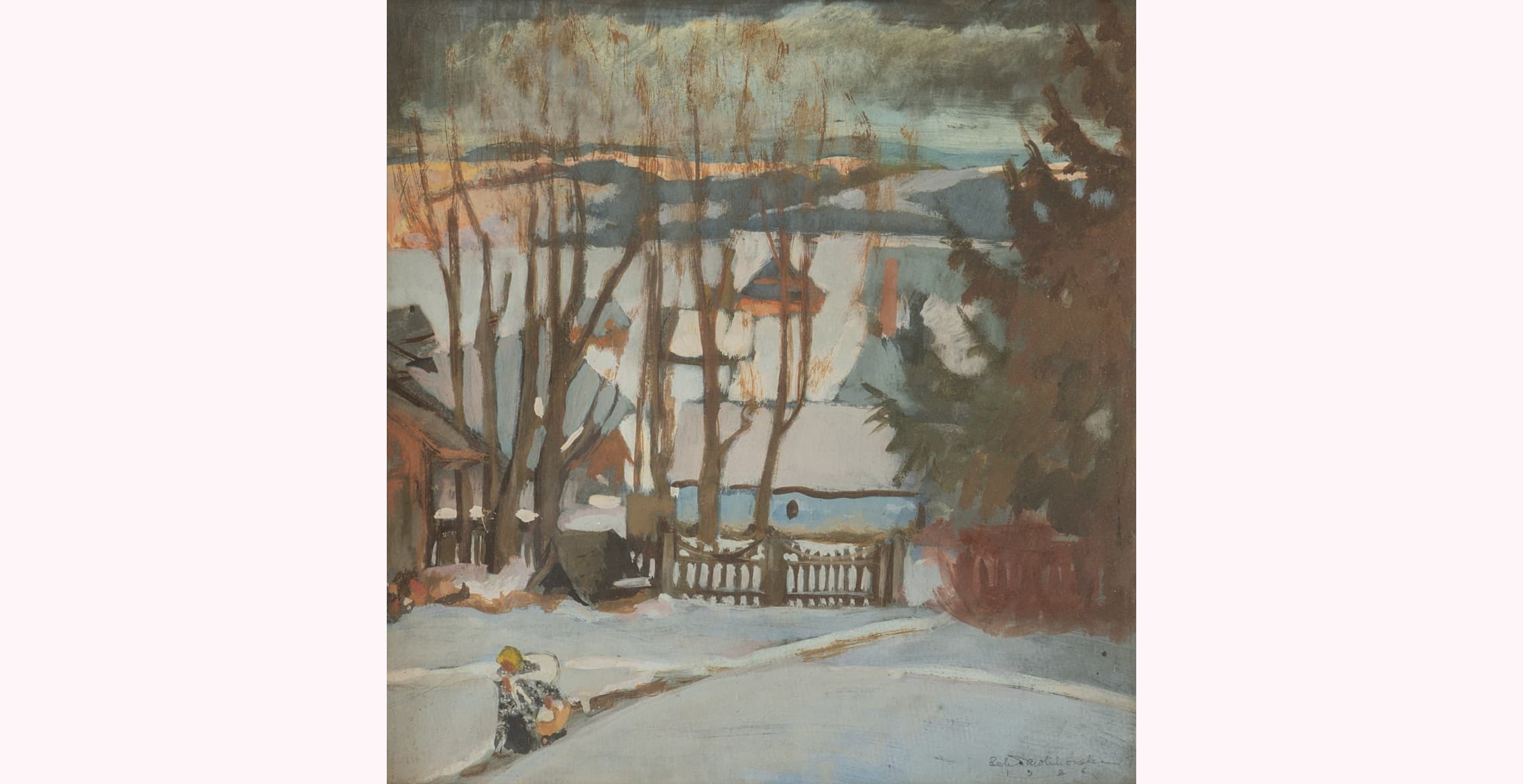

Over the years, she also painted watercolor landscapes of Medyka, Zakopane and southern Europe [Figs. 16, 17, 18]; representations of plants and animals; and numerous genre scenes revealing the artist’s sly wit. A deeply religious person, Lela Pawlikowska considered her most important work to be a series of ten linocuts hand-colored with watercolors, published by Michał around 1934 as a graphic portfolio entitled Bogurodzica (Mother of God). This series can be considered one of the most outstanding representations of the Art Déco style in Polish graphic art. The only published statement by Lela about her art concerns this very work. Here she emphasizes that in art she seeks ‘a combination of pictorial elements with an expression and Polishness […],deriving pattern or style from no source unless from folk art, […] in order to act with the simplest of painting means, that is, with a clear line, while at the same time demonstrating expression as much as possible’.

War, the first utilitarian application of Lela’s talents

The outbreak of World War I shattered the home life of the Pawlikowski family [Fig. 19]. It deprived them of their home and of the material basis for their existence, and separated the family for a long time. Michał had to flee Poland due to his political activity in the conservative endecja movement, and eventually ended up in Italy, where he started efforts to bring his family over. Lela, together with her children, one of whom was disabled and required constant care, initially took refuge in her family home in Zaświecie, where her sister Beata lived. The Soviet invasion quickly made this refuge illusory.

This was the moment when a fundamental breakthrough in Lela’s artistic approach occurred.

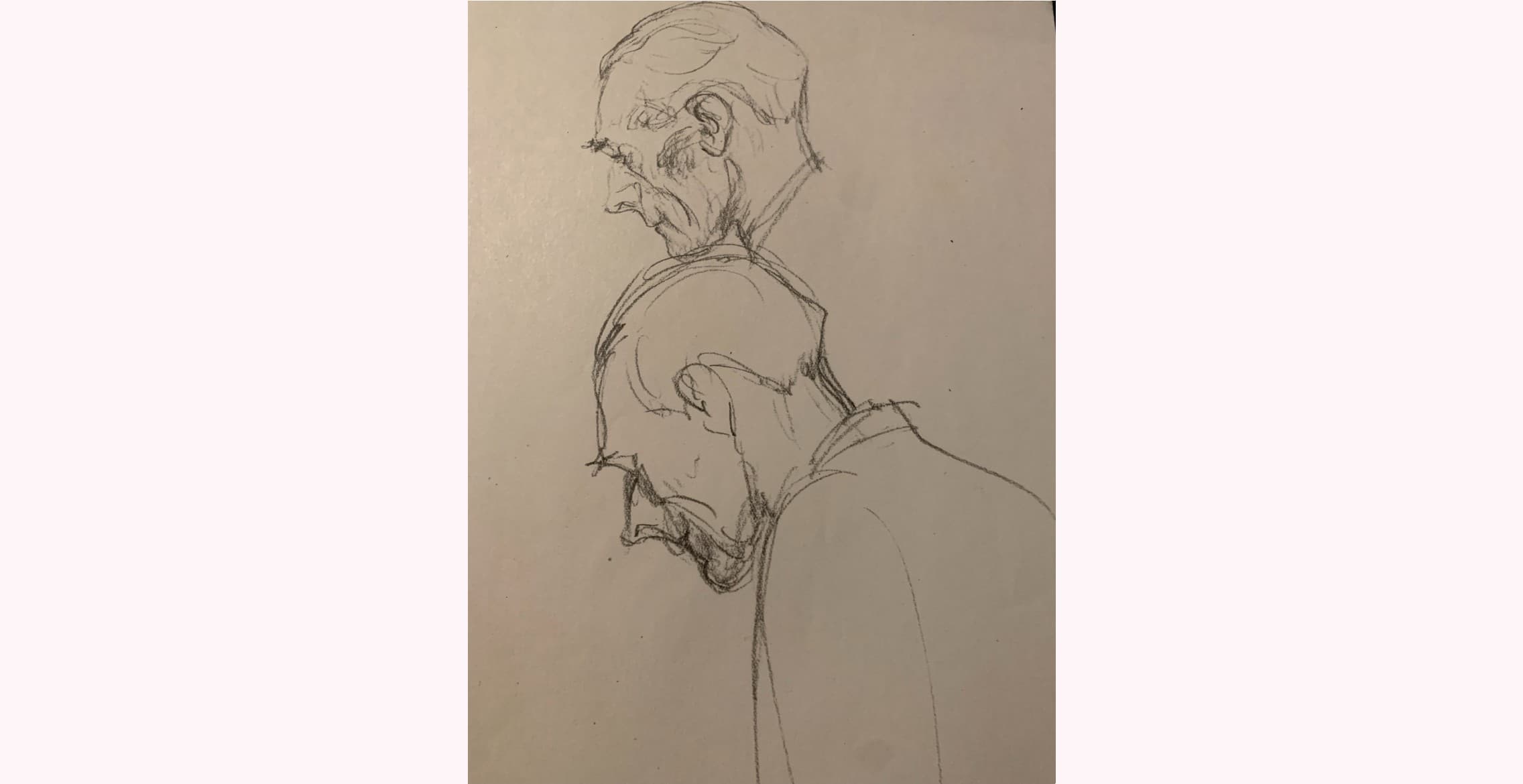

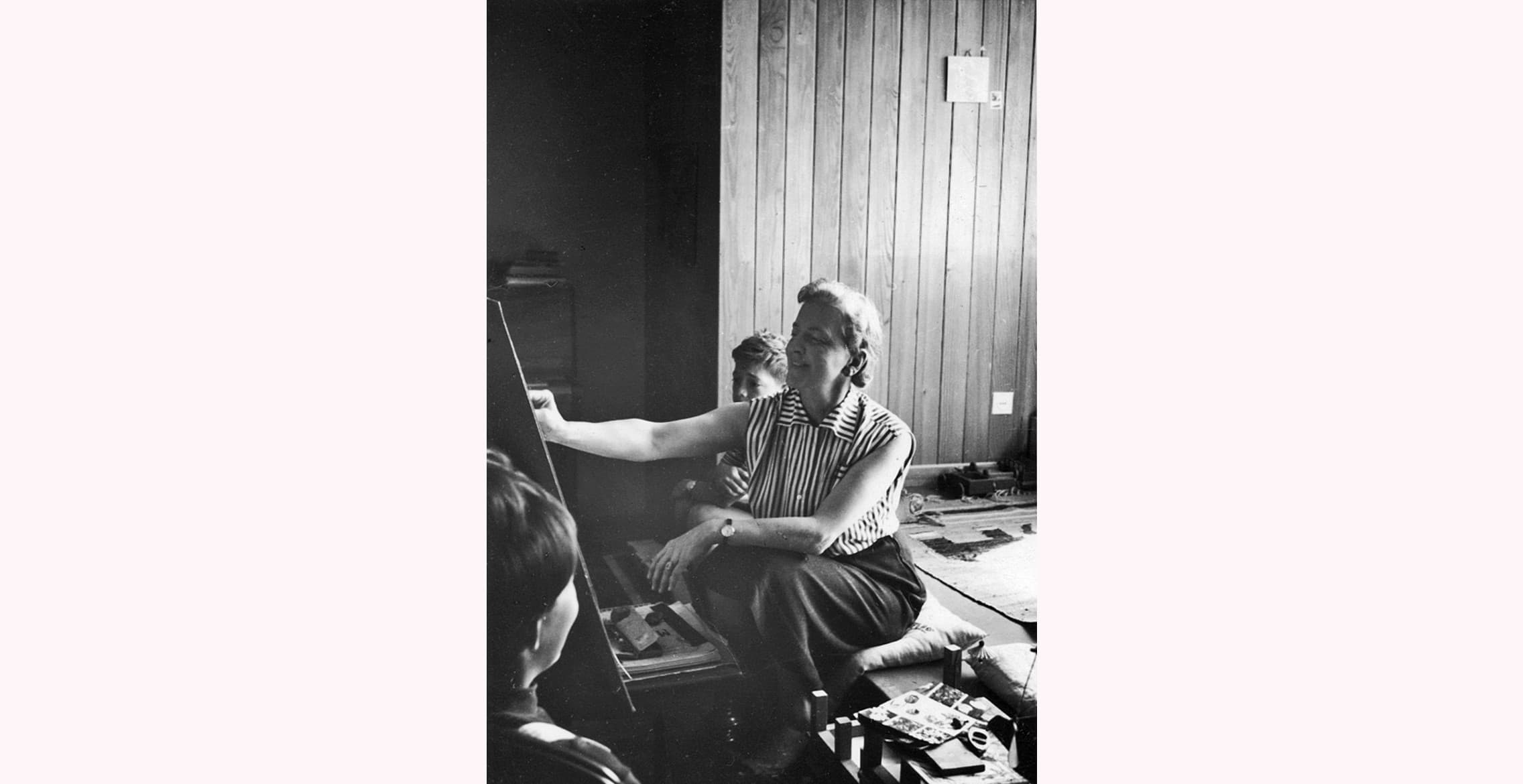

Tireless and relentless in her work, she, like her first teacher, Władysław Witwicki, never parted with her sketchbook [Fig. 20]. In occupied Lwów, Lela recorded views, scenes, and characters in exchange for children’s shoes and food. Before the war, the growing fame of this outstanding portraitist brought clients to Medyka, but she never had to earn money through her art. Now, facing hunger and cold, and with a chronically ill child in her care, she discovered that her talent could be used to meet her family’s most vital needs. What she did not know was that she was entering a treadmill, from which she would not break free for the rest of her life.

Confronting escalating Soviet repressions, she decided to take advantage of a brief opening of the border between the German and Soviet occupation zones and moved with her children to Kraków. There she lived with her four children on her cousin Zofia Kernowa’s estate in Goszyce. Despite the horror of the Nazi occupation, the manor house in Goszyce was a relatively safe haven in which many people in need found shelter – intellectuals from Kraków, Home Army soldiers, and even the Jewish Glücksman family, which was then punishable by death. There are reproductions of several portraits in the family photo archive, which Lela likely made to commission at that time, thus affording her a modest means of income [Fig. 21]. She also sketched a lot, often illustrating current events by means of accurate genre scenes.

In the spring of 1942 the family was granted permission to leave Poland and join Michał in Rome.

Emigration to Italy, starting a career as a high society portrait painter, with artistic invigoration in the background

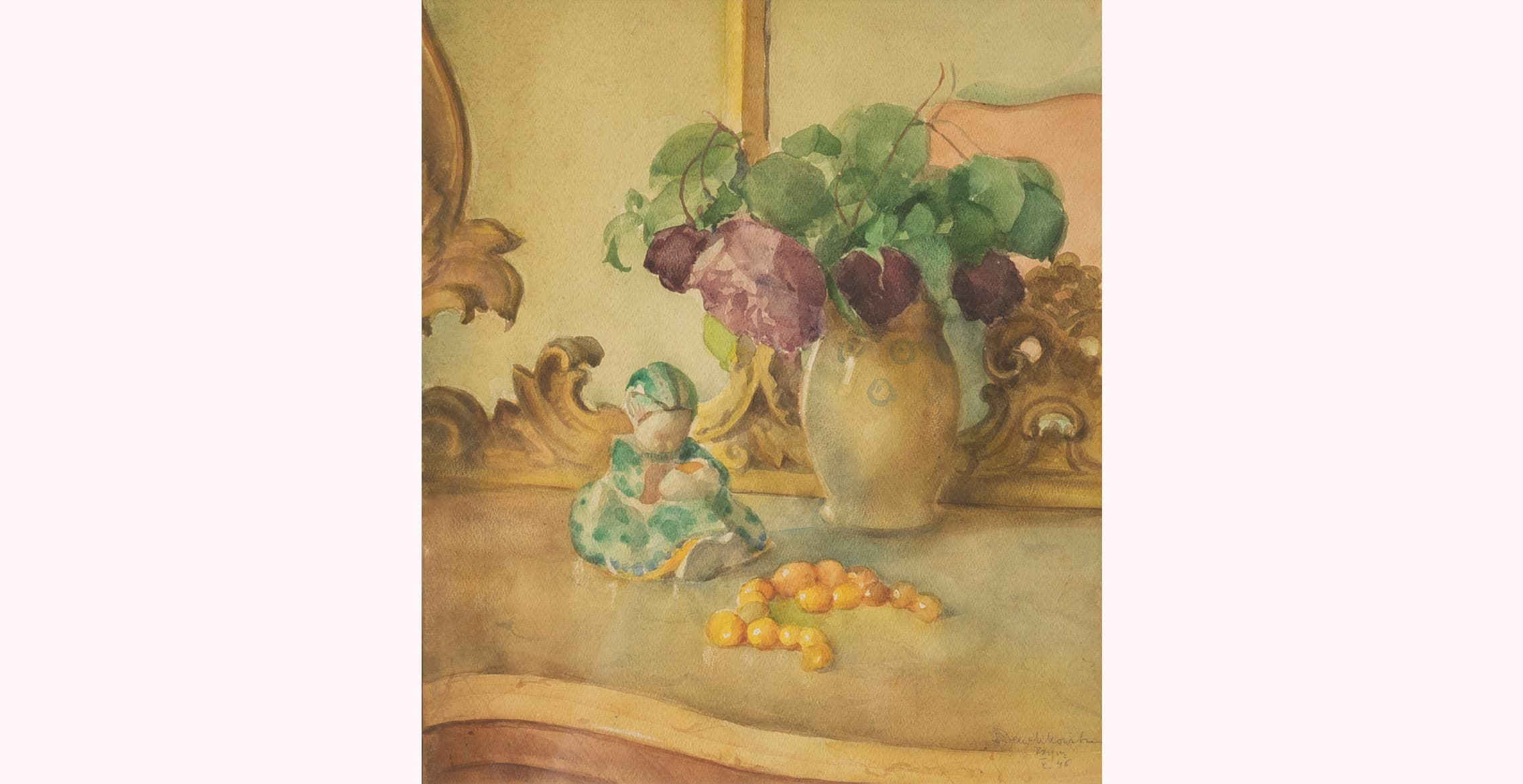

In Rome, Michał Pawlikowski made earned a modest living working for the Polish Primate’s Committee for Aid to Refugees, and subsequently as a teacher in a Polish high school. It was far too little to support a family of six. Soon Lela’s fees for portraits became the family’s primary source of income. The first of these paintings, which paved the way for the artist to enter aristocratic salons, was a portrait of a Polish woman, Zofia Pietrabissa Finocchietti (née Daniszewska, primo voto Znaniecka) [Fig. 23]. Many of Lela’s portraits were created during this period. Her clients were, among others, the Borghese, di Borbone, Torlonia, Marone-Cinzano, Theodoli and Nunziante di Mottola families. Many of these portraits, as we can determine on the basis of the surviving black-and-white photo reproductions, are characterized by a certain stiffness – a painterly distance – although there are some outstanding works among them. Marta Trojanowska, the author of Lela’s biography, has noticed that it was during the Italian period that still life developed as a subject in Lela’s work, having hardly preoccupied her before the war [Fig. 24]. Such sketches first appeared in Goszyce, but it was only in Rome that this trend in her painting gained strength, yielding some interesting works. This is insightful; it demonstrates that at the beginning of her professional career as a portraitist, Lela found a lot of creative energy within herself – its emanation was to take up this purely artistic topic. These paintings, with subtle colours, exude nostalgic peace (Figs on a plate, Figs in a basket, Still life with ambers).

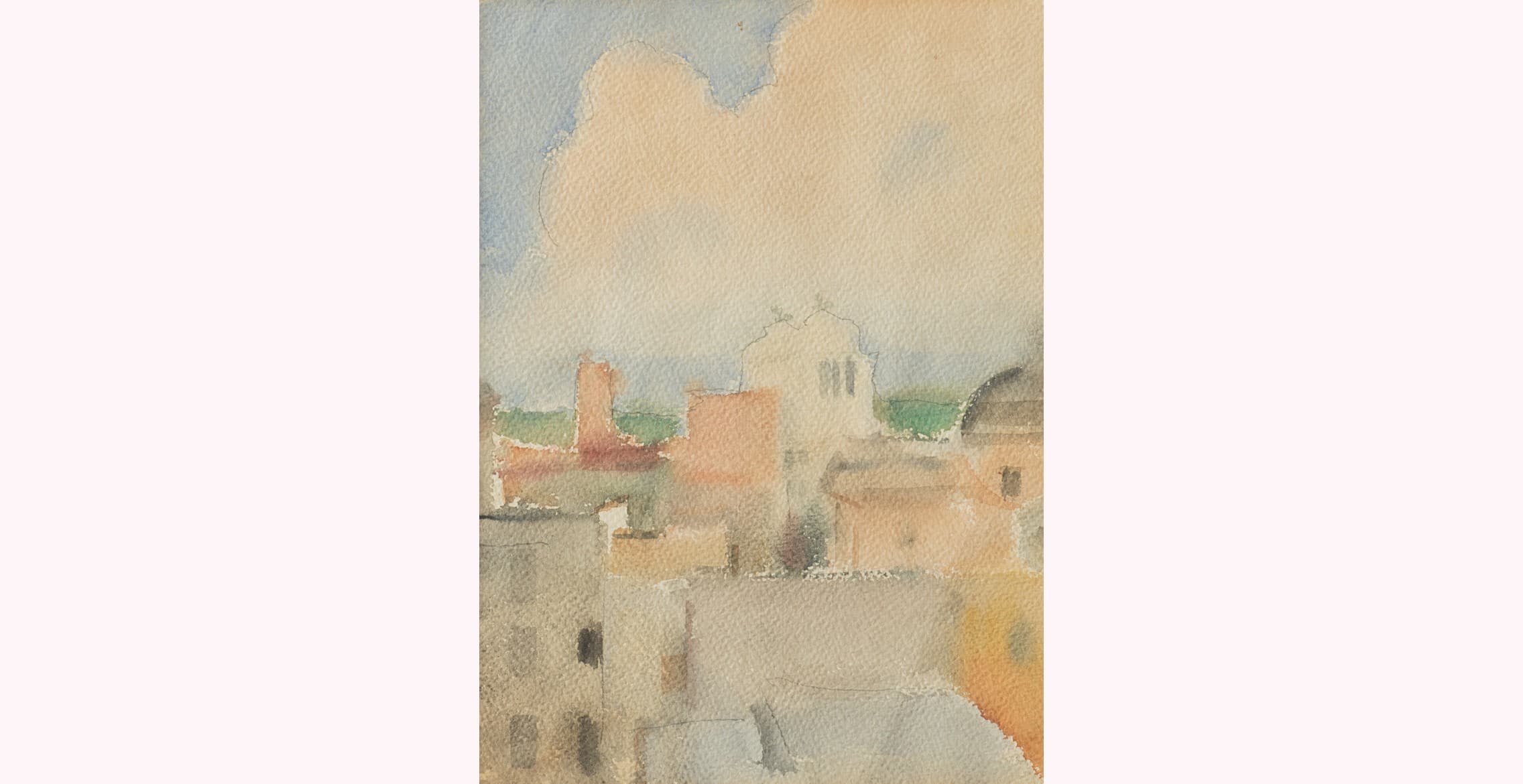

However, there are only a few Italian landscapes – and these are completely different from the pre-war period. They depict the city almost exclusively from a distant, deserted perspective seen from the Gianicolo Hill, where the Pawlikowski family lived for a long time. No painterly reminiscences of Lela’s journeys to the south of Italy for her clients have survived.

It seems that despite wartime challenges, the Italian period was perhaps the happiest stage in Lela Pawlikowska’s life as an émigré, at least in terms of her art [Fig. 25].

Although she did not have a studio, a relatively steady income together with the spacious Roman apartments that her family rented thanks to her earnings, guaranteed her relative creative freedom. Kasper Pawlikowski, Lela’s son, recalled that the best solution for her would have been to stay in Rome after the war [Fig. 26] She left her two daughters on Italian soil. Agnieszka, whom she looked after with such dedication until her untimely death in 1944, is buried in Campo Verano, and Maria Ludwika, Lula, entered the convent there in 1945.

Unfortunately, there was no such possibility. Italy defended itself against the influx of war survivors by denying them the right of permanent residence. However, because her son Kasper was a soldier of the II Corps, Great Britain admitted him, Lela, Michał and their nine-year-old daughter Dorota. Beata Obertyńska, Lela’s sister, also wearing the uniform of the Polish army, was already there.

Emigration to Great Britain, development of a career as a portraitist at the expense of creative freedom, disability, the role of the iron curtain

For 45-year-old Lela, re-emigration was a difficult step [Fig. 27]. London was swarming with Polish refugees, it was difficult to find employment, and it was necessary to become financially independent as quickly as possible. The artist did not have extensive contacts here, and British high society – her potential clientele – was much more hermetic than in Italy. Thus she started taking advertising commissions. As an illustrator she sought employment with English publishing houses and designed postcards and Christmas cards. The only commission she refused was to paint ties. Although her husband initially found work at the Polish publishing house Veritas, Michał’s difficult personality soon led to unemployment, while his inexhaustible political, cultural and charitable activity generated costs. Lela, however, was determined to bear them, remembering the support she had received from him at the beginning of her creative path.

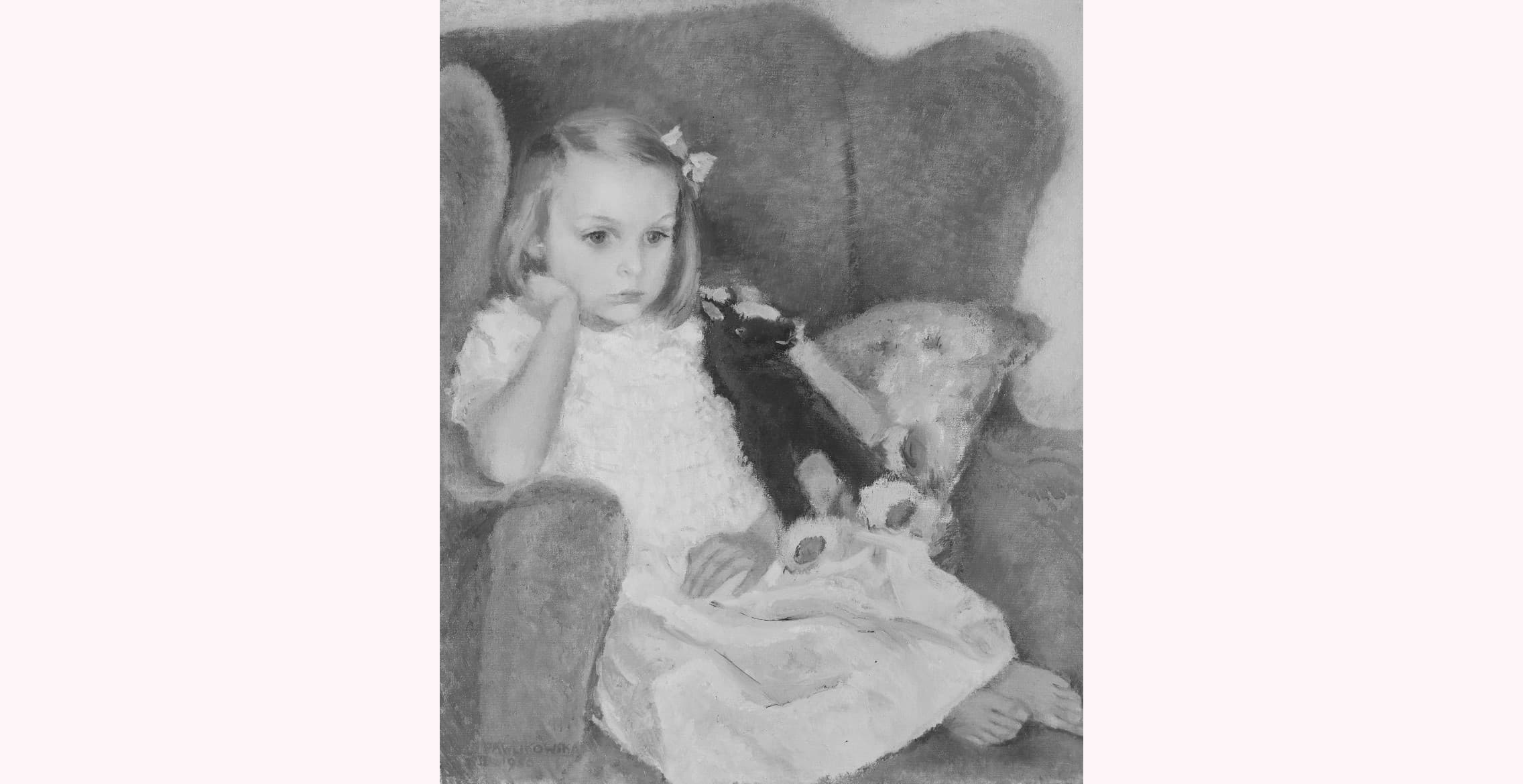

She sought clients in the same way she had in Italy – by portraying Poles who were associated with figures in British society. We know of a few paintings that were created in the beginning of her stay in England like Portrait of Mme S. George [Fig. 28], Portrait of Stefania Rudnicka, [Fig. 29], as well as the compelling portrait of little Ann McLaughlan (1950) [Fig. 30]. The latter was displayed at the exhibition Portraits of Children organized by The Observer in June 1950. A year later, The Studio published an article about Pawlikowska’s work, illustrated with the same three portraits. This led Lela onto her new path as a child portraitist. She made several hundred paintings of this kind. Her method of working with a model was methodical: at the clients’ home she observed their behaviour and character, then she made several sketches, from which they chose one. The artist then developed this into a portrait and subsequently selected frames and made photographic documentation. Over the years there was no significant evolution in the artist’s commissioned portraits. Their conventional form guaranteed an influx of new clients, and thereby provided financial security for the family.

As in Italy, in their London apartment at Clifton Gardens, Lela did not have a studio. The entire arrangement of this small apartment was subordinated to her husband’s unprofitable but absorbing activities [Fig. 31]. At that time only the youngest of their children remained their dependent, but a significant part of Lela’s earnings were allocated by Michał to the maintenance of the large wooden villa Dom pod Jedlami in Zakopane (built by his father) [Fig. 32], where the Pawlikowski Archive he had created was housed. He also helped their family and friends in Poland on a regular basis. For years, the Pawlikowski couple supplied them with medicines and scarce goods. They also paid salaries to the archivists who were employed in Zakopane. In the early 1950s, Lela started working as a drawing teacher at the Farnborough Hill College girls’ school (where her daughter was also a student). This work, two days a week, could have provided Lela with greater stability and retirement security, but she had to give it up because the British immigration authorities did not give her permission to take up a profession other than as a freelancer. The interventions by the highest level of the Polish government-in-exile did not help. Once entered in her documents, her employment status could not be changed.

Meanwhile, Lela Pawlikowska’s artistic career continued to develop. The 1950s were probably her peak period. Charming and well-mannered as well as talented, Lela attracted clientele from ever higher ranks of British society [Fig. 33] – the Princess of Kent, the Spencer family [Fig. 34] (including Lady Diana Spencer as a child), artists, diplomats, and senior army officers. From each commission followed another, also from outside the UK. The artist travelled to Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, the Netherlands, and also returned to Italy. More and more articles appeared in the press. [In 1955, at the instigation of the Costa Rican ambassador, Lela’s largest solo exhibition was held at the Parsons Gallery, followed by a flood of reviews [Fig. 35].

This good streak was interrupted by an apparently harmless fall in 1958, which caused Lela to lose sight in her left eye [Fig. 36]. Surgery did not help, and only made matters worse. Lela’s Italian friend and aristocratic client, the Duchess de Vito Piscicelli, came to her rescue and financed plastic surgery in Rome to conceal the visible effects of her disability. The artist returned to her former work as a portraitist, but preferred not to work with children, for their mobility proved too difficult.

In 1957, she started visiting Poland on a regular basis with Michał, spending long months at the Dom pod Jedlami in Zakopane. There, too, Lela did not have adequate space for her work, but she nonetheless created many portraits of her family and friends.

In 1970, Lela’s beloved husband died in a car accident in London [Fig. 37]. As it often happens in the case of such asymmetrical relationships, his death meant for her an even stronger commitment to his legacy. She continued to pay considerable sums for the maintenance of the Pawlikowski Archives and the villa itself. She organized Michał’s papers, facilitating the publication of his works, and articles about him and his achievements. She was not particularly interested in promoting her own work. At the urging of her daughter, Lula, the nun who studied at the Royal College of Art in the 1970s, she took part in only one group exhibition of Polish artists at POSK (Polish Social and Cultural Association) in 1975, exhibiting several of her graphic artworks there.

With no pension to sustain her, she took portrait commissions almost until the end of her life [Fig. 38]. The circle of her clients narrowed ever more. Her sketchbooks show depressing cityscapes, both of London and of Canada, which she visited several times. It would seem that she did not see any eye-catching views or motifs – although she still travelled to Zakopane and to the English countryside. She continued to live with her sister Beata at Clifton Gardens. During the last months of her life, after her sister’s death, she found shelter in a residence for Polish emigrants known as ‘na Antokolu’. She died a day before Christmas Eve in 1980.

Absence, fading into oblivion

The work of Lela Pawlikowska is divided into two stages by World War II [Fig. 39]. In the first stage, she developed her technical stills, gained creative experience, had a growing share in artistic life, and gained a reputation as an outstanding portraitist. The Soviet and German occupation forced her onto a path of making portraits for profit. Initially this was on a small scale limited by occupation, but subsequently during her life as an émigré in Italy, it became the basis of her family’s existence. However, she still found enough creative energy within herself to undertake landscapes and still lifes. This energy began to fade only in the face of the hardships of re-emigration to Great Britain, although not immediately. The series of undoubted successes in her career as a portrait painter in the first decade of her stay in England was interrupted by the loss of sight in one eye. The artist, however, made every effort to ensure that her disability did not become an obstacle whilst painting portraits for a living. She saw no alternative.

In Poland, however, she completely disappeared from the artistic horizon. Her works remained unknown and never entered the world art market except for some portraits painted on commission. Due to communist censorship, there was no access to her works in national galleries and museums in her homeland. This was a consequence of the émigré activities of Michał Pawlikowski, and the publication of Beata Obertyńska’s book In the House of Captivity. Published in 1946, it is one of the most riveting testimonies of Stalinist crimes.

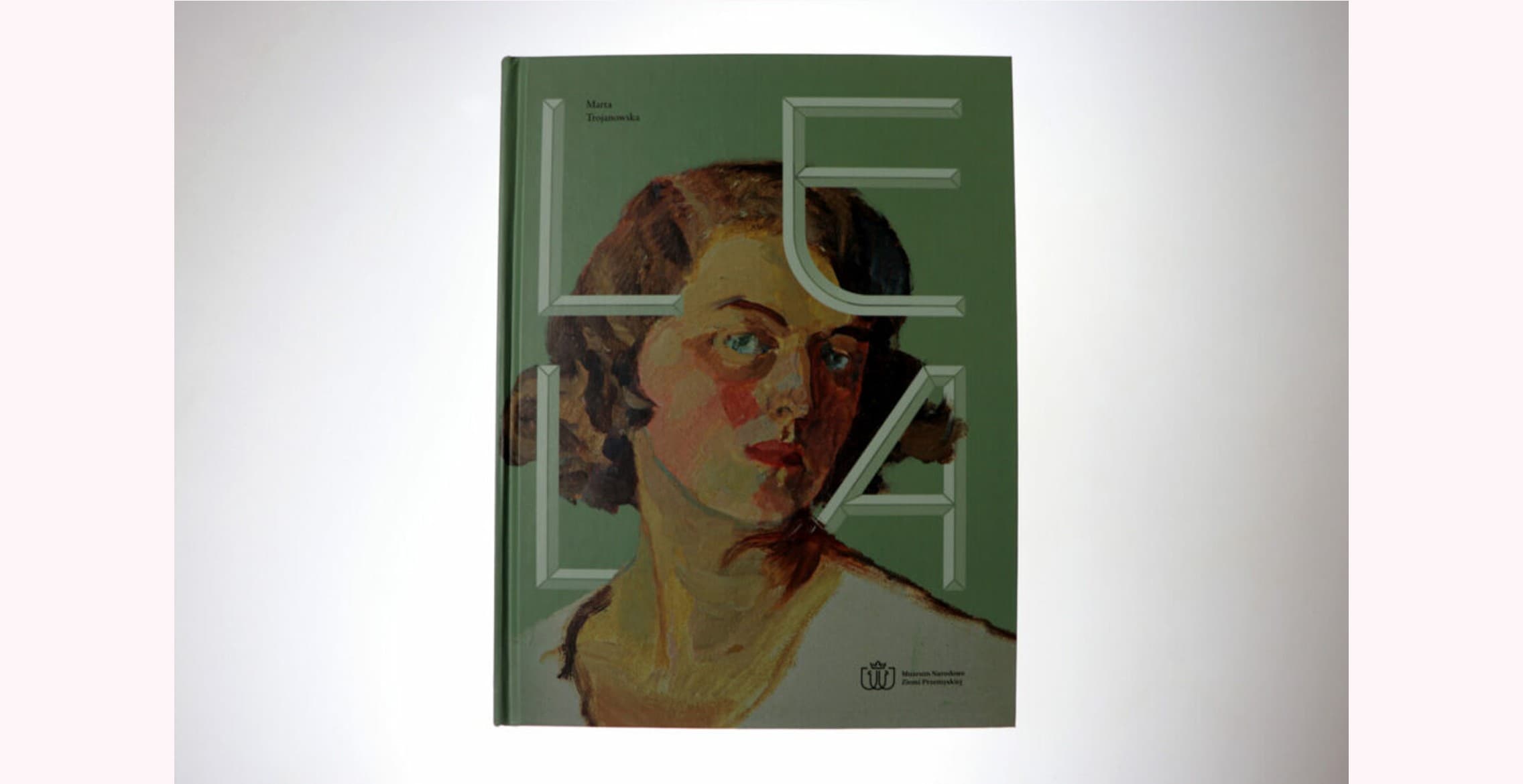

A breakthrough came only after the collapse of the Communist regime. In 1997, almost two hundred of her works were shown at the exhibition The World of Lela Pawlikowska, firstly in Zakopane and then in Przemyśl – the result of a gift that the artist’s son, Kasper, made to the National Museum in Kraków. When Dr. Marta Trojanowska, the curator of the National Museum of Przemyśl, became interested in her work, Lela’s works began to be included in more and more group exhibitions organized at this museum. The culmination of Dr Trojanowska’s efforts was the enormous retrospective exhibition ‘Straight from myself’ – The work of Lela Pawlikowska née Wolska, which took place in Przemyśl (11 March 11 – 3 May 2022). This event was preceded by the publication of Dr Trojanowska’s monograph Lela: The life and work of Aniela Pawlikowska née Wolska (1901-1980) (Przemyśl 2021) [Fig. 40].

It is time for this modest but outstanding portraitist to find a place in the world of Polish art. I certainly hope that the exhibition of her work prepared in Przemyśl by Dr Marta Trojanowska will lead to additional exhibitions in Poland, and that it will help restore the memory of this artist. Perhaps it will also bring renewed attention to her many achievements, hidden away in private European collections yet to be discovered.

Aniela Pawlikowska is a classically trained musician and poet. She is Aniela Pawlikowska’s daughter-in-law, and the great-granddaughter of the novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz.